Frustration Generator: Sprinky Physics Game

Sprinky is an attempt at creating a physics game where the player controls a spring like object. The game itself is quite playable, at least in the sense of a working prototype with multiple levels. The physics play mechanic, though, falls short of my expectations. The learning curve is too brutal, and the kinesthetic feel is distinctly clumsy. I’ll try to explain some of the design decisions involved in the making of Sprinky to shed some light on prototyping a physics mechanic.

Designing the Physics Rig

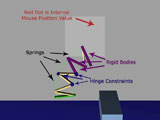

The inspiration for Sprinky was, quite obviously, to mimic the behavior of a real-life Slinky. My friend Steve Swink had actually created a Slinky-like contraption in Virtools, but I wanted to try another method for controlling its motion. The problem with designing physics-based control schemes is that it’s difficult to make the motion appear muscular in nature. It’s easy enough to apply external impulses or torques to objects, for things like jumps and turns. The resulting motion looks odd, though, as if driven by a puppeteer. I wanted to limit the object’s physical exertions to its own contractions and expansions.

Havok powers the physics engine in Virtools (well, more specifically the engine is Ipion, a company/engine Havok bought out years ago). To accomplish the sense of an internally-influenced physics rig, I used springs on the left and right sides of the sprinky.

Moving the mouse up and down extends and contracts the length, and moving the mouse left and right alters the ratio of lengths between the left and right side. The result is a realistic sense that the sprinky is applying force to the world around it, rather than having arbitrary external forces applied to it.

This first physics test is playable with the Virtools Web Player. The source CMO is available for any Virtools developers out there, too.

Adding Gameplay Elements

The next step was to add some flavor to the gameplay. I decided to go a very simplistic route in designing the rules for interacting with the environment. There are five types of object flags in the game: normal, ice, rubber (all variants on friction), and two types of game-over-if-touched flags (one for if any piece of the sprinky touches, and one for if any of the middle pieces of the sprinky touch).

The flat-poly prototype with the test levels is playable with the Virtools web player. The end result is a surprising amount of flexibility in designing courses. It’s possible to ramp up the game’s difficulty by using combinations of the two game-over flags. The actual difficulty in playing the courses arises from the failings of the core mechanic, though, so let’s talk about that.

Damned Hard

It’s obvious to anyone who’s played Sprinky for even a few minutes: The game is hard. And frustrating. While it is possible to complete all of the levels, sure, you have to be something of a masochist to actually enjoy the experience. It’s very hard to learn how to control the sprinky, partly due to some problems with the physics design.

Before we get into specifics, I do want to say that I think there is something to be said for the nebulous quality of how “well-tuned” a physics mechanic is. The quantifiable components that go into tuning a physics mechanic can be vague. Is a spring constant of 0.13 more or less enjoyable than 0.12? There is definitely an element of gestalt at work that can be difficult to componentize.

Mouse-Flip Problem

One design problem with Sprinky’s controls was how to handle the sprinky flipping over. If the player does a 180 flip, should left and right still correspond to the sprinky’s left and right, or should they correspond to the world’s orientation? This problem is nonexistent in games like Ski Stunt Simulator, since the avatar has an obvious top and a bottom.

One available solution was to color-code the sprinky or otherwise indicate which end should be up. It seemed counter to the goal of using a Slinky-like object in the first place, though. After all, one of the distinguishing features of a Slinky is its ability to walk end over end.

The solution I implemented was to flip the mouse X axis when the sprinky itself flips over. The crippling downside to this occurs when you lie near horizontal, though. The mouse cursor will constantly flip. It’s very hard to right yourself in the game when you fall over because of this.

Unresponsive Movement

Generally, the sprinky feels unresponsive. This is due to a few factors. Primarily, the rig has a lot of jitter and bounce in it. Movement takes awhile to pass through all of the joints and springs, causing wave and jitter motion. It feels more like you’re guiding the sprinky than directly controlling its actions. As a result it’s very hard to get accurate movement and to really connect with its motion. The kinesthetic feel is completely missing because of the lag between moving the mouse and waiting for the rig to catch up and stop oscillating.

What to Change

This all begs the question: What would I change if I were to spend more time on Sprinky? This may sound odd, but the first thing I would do is completely scrap the current rig and rebuild it. In my experience it’s very difficult to massage numbers on a physics control setup that “feels” bad until it feels good. It’s much faster to rebuild everything. If I don’t manage to get that juicy physics-based feeling within the first day of development I’ll start over with a different approach. It’s just too easy to lose all objective reference as time goes on.

All Tarted Up

My friend Creath Carter created some fantastic artwork for Sprinky (he also did the artwork for Rolling Assault). The sexed-up version of the game was entered into the Independent Games Festival 2004. The art version of the game is available exclusively on Fun-Motion. Feel free to chime in with your thoughts on how to fix the control system, too. I’d love to hear people’s opinions on what exactly is so hard.

Download Free Sprinky Game (4.3 MB)

Related Posts:

Great-Looking Motorcycle Game, But Is It Fun?

Motorama is a very well-produced motorcycle trials game by Januar Tanzil. Physically, it falls somewhere between Elasto Mania and Trials in terms of the fidelity of the simulation, but more on that in a sec. Motorama’s website describes the game as follows (the author is Indonesian, hence the odd English):

Unlike racing simulations, Motorama is features puzzle like gameplay, where deciding where you give it the gas and how to position your landing creates the best strategy to reach the finish line in the fastest time possible.

Physics: Ugh

I’ll be blunt: I don’t like the physics in Motorama. They’re far too firm; there’s no sense of a suspension system whatsoever. I’m not quite sure what’s going on behind the scenes, but rather than behaving like a spring-mass system the bike and its wheels behave extremely rigidly. The bike’s impacts have no give to them. The wheels bounce off the terrain like two granite boulders.

Also, the rider appears to have no impact on the physics system. His position doesn’t affect the balance of the bike, and his motion doesn’t feed back into the physics system. In other physics motorcycle games, like Trials, the rider’s physics will actually dampen the bike’s motion.

Masochistic Difficulty

Motorama is hard. Not that good kind of hard, either. The game feels more like a beat down than a surmountable challenge. The difficulty stems primarily from the game’s physics. It’s difficult to predict the bike’s behavior, and it’s too easy to experience sudden changes in movement (particularly due to the heavily polygonal terrain). Subtle variations in speed and angle will have dramatic consequences. The physics feels very intolerant.

The controls could also be improved. Currently, the boost is activated by a double-tap of the acceleration key. I would much rather have boost controlled by a second key so I could tap it at will. Right now, you can’t exactly tap boost on and off–if you tap acceleration three times it’s going to keep boosting (assuming the last two taps were for another boost, I guess). It’s too hard to control your speed.

But, So Pretty!

I really want to like Motorama. It’s a beautifully produced game. The graphics are lush, the levels are varied and numerous, and it’s full of polished little touches like particles, an animated day/night cycle, and well-made audio.

Sadly, the game is more frustrating than fun. The physics just aren’t there. I don’t know much about the game’s development, but I get the feeling Motorama was isolated from player testing and feedback during its creation. The developer probably ratcheted up the difficulty until it was hard for him, which leaves the rest of us out in the cold.

Download Motorama Game (11.5 MB)

The above download link is a free demo of Motorama. The full version is $19.95.

Related Posts:

Builder Physics Games Evolved: Armadillo Run

Armadillo Run is a build-and-simulate puzzle game in the same vein as Bridge Construction Set and The Incredible Machine. In fact, the game essentially plays as a hybrid of the two. The goal of the game is to guide the armadillo–it’s basically a basketball–to the target area. To accomplish this you have a limited budget to spend on building materials like metal struts, cloth, rope, and rockets. Like most physics games, the open-ended nature of the simulation allows for multiple creative solutions to any given level. Armadillo Run is fun even when it stumps you.

New Flexibility = New Complexity

Armadillo Run’s physics engine resembles the classic physics game, Bridge Builder. Even when compared to Bridge Builder’s most recent incarnation, though, Armadillo Run wins out in terms of sheer features. The game has cloth, rope, and elastic (although technically these are all simply tightly-knit series of spring segments). Other options are available, too, including setting the tension of joints and setting timers to remove specific joints after a desired amount of time.

These features do allow for more flexibility in solving a puzzle, but they also introduce more complexity. It can take a few budget-breaking attempts before what you’re supposed to do becomes obvious. Depending on your appreciation for puzzle games, this will either infuriate or delight you; a lot of fun is learning how to use these building materials in clever ways.

Finally, a Usable Interface

The interface in Armadillo Run is slick. Rather than forcing you to draw on a grid, you can simply draw supports wherever you like. The game will automatically segment pieces while you draw them. The metal support structures have a maximum length. This makes dense construction slightly more difficult. The payoff is it’s much faster to create larger structures, which most of the levels require.

Other niceties are present, including the ability to drag a midpoint around after it’s already been drawn. The game features a single level of undo, which is unfortunate. It would really benefit from a proper undo stack, especially when you realize your supposedly-clever structural addition is a complete failure.

Sloppy Goals

The player goal in Armadillo Run is very loose, particularly in contrast to other physics-based puzzle games. The goal is to get the ball–come on, that’s a pretty weak-looking armadillo–into the end zone for five consecutive seconds. Basically, as long as you can fudge it for a full five seconds you can pass the level. Many of my solutions feel slightly unstable, but I guess that’s part of the game’s allure.

I do miss having a clear route to goal for each level. Many of the levels in Armadillo Run drop you off at the proverbial curb and force you to find your own way home. While it is fun to create free-form structures, I would have liked to see some levels focus more the structural stability elements of the gameplay.

Level Editor and Other Goodies

To be fair, I don’t have much ground to stand on when it comes to complaining about the game’s stock levels. The developer, Peter Stock, included a level editor with the game. If I really wanted to see more levels focus on stable construction chops, rather than clever tricks, I could make some levels more along those lines. The Armadillo Run website has a database area where other players can share their levels and solutions, too. The game launched less than a month ago, so it remains to be seen how prolific the game’s community will become.

(Armadillo Run Game Screenshots)

Run Armadillo Run!

Armadillo Run represents the evolution of puzzle physics games. It is both familiar and new, and offers something fresh for players bored with building bridge after bridge.

Download Armadillo Run game demo (1.56 MB)

The full version is available for $19.99 from the Armadillo Run website.

Related Posts:

- Heading Down Under!

- 2007 IGF Finalists Announced

- Indies Have Opportunity with Physics Games

- Beautiful, Frustrating Puzzle Physics

- Interview: Peter Stock, Armadillo Run

My name is Matthew Wegner, and this site is dedicated to physics games.

My name is Matthew Wegner, and this site is dedicated to physics games.